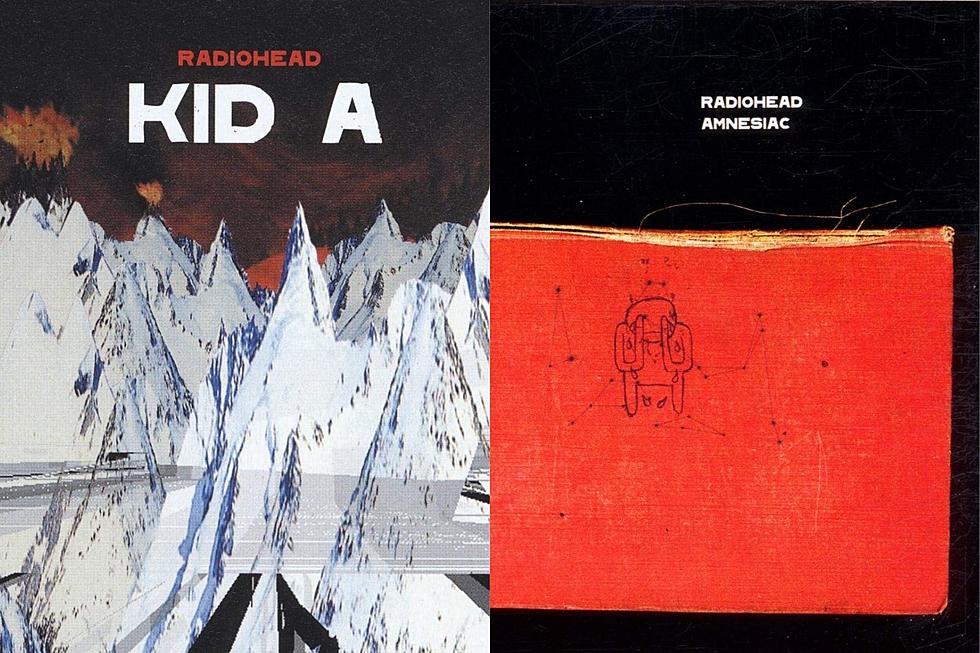

Why Radiohead Chose to Avoid ‘Arrogance’ of Double LP for ‘Kid A’

Radiohead didn't have much in the way of an organized plan after the surprising success of their third album, 1997's OK Computer. The significant sonic shift from guitar-centered and lyrically relatable earlier records to a more abstract and experimental style had placed the band in entirely new territory as the 20th century came to a close.

Three years after the release of OK Computer, Radiohead reconvened to work on the next album, whatever that might yield. "We're very bad at setting, you know, manifestos about what we're going to do and what we're going to change," guitarist Jonny Greenwood told KCRW in October 2000. "We drift along, really."

The resulting record, after more than a year of studio work, was 2000's Kid A, and it was full of ambient sounds and electronic noise that further diverged from Radiohead's initial rock-focused approach.

“There was no sense of, 'We must progress,'" singer Thom Yorke told Select in December 2000, a few months after the album's release. "It was more like, 'We have no connection with what we've done before.' What we're hearing in our heads is much more like this disjointed, fragmented thing – very much a landscape."

Listen to Radiohead's 'The National Anthem'

Disjointed, however, didn't mean unproductive. Radiohead wound up enjoying writing so much that they had amassed more songs than a single album would allow. "We're still not sure how we're going to release them or what order we're going to put them in, or how long the record's going to be," Greenwood said at the time. "But we certainly had too much for one record."

For bassist Colin Greenwood, "the big fear is it's easy to go and record, but it's very difficult to envisage what's going to be released and end up in the CD case in a record shop – and so that's really the problem," he told KCRW. "There's no problem with all hanging out and eating beautiful food every day, and making music and working on computers and playing guitars ... but it's a big problem thinking about editing and compiling and presenting."

The natural solution with a surplus of material was to make a double album, but that idea that was swiftly nixed by the band. "There's an arrogance in them," Jonny Greenwood told KCRW. "Bands get to a stage where they think their music is worth, you know, three hours of your time, and it's not really."

That put Radiohead in the delicate position of selecting which songs to keep and which to set aside, an effort Yorke said required the inspiration of another band that knew a thing or two about making large leaps during short spans: the Beatles.

Listen to Radiohead's 'Idioteque'

"Even though they're really great songs, and I'm really proud of them, they just didn't fit," Yorke said of the songs that didn't make it onto Kid A. "Which is quite a weird feeling, because you think an album should be just basically the best songs. That's not necessarily true. You can put all the best songs in the world on a record, and they'll ruin each other.

"On the later Beatles albums, when they got really, really good at putting things next to each other, like on the White Album, it's just amazing. How in the hell can you have three different versions of ‘Revolution’ on the same record [sic] and get away with it? I thought about that sort of thing.”

That still left the sequencing of Kid A to be dealt with. It began easily with the opening track, the sparsely arranged "Everything in Its Right Place," but quickly proved a challenge for everyone to agree on. For one, even though songwriting credit was equally distributed among the five members, it was often Yorke who would come to the table with a song started.

"We always kind of wrote our own parts, there was a creative outlet for that," guitarist Ed O'Brien told The Face in 2020. "But that’s the way Radiohead was set up. I’m not comparing us to the Beatles, but John Lennon put it beautifully when someone asked about George Harrison songs: 'The empire was carved up between me and Paul [McCartney].' That’s the way that certain groups work, and that’s the dynamic."

Listen to Radiohead's 'Everything in Its Right Place'

With so many songs, there were bound to be discrepancies in terms of order, a period Yorke referred to as "a nightmare." O'Brien agreed, telling The Face: "I think [doing] the track listing of Kid A was really fraught. That felt like it could go either way. It could break – like it would snap, and that would be it. But we came in the next day, and it was resolved."

The spontaneity drove the disorder of the album and eventually elevated it. Radiohead's lack of attachment to specific instrumental roles, plus their obvious willingness to incorporate nontraditional rock arrangements, left the band wide open for whatever felt best. "We had one of those horrible whiteboards you have in offices," Yorke told Select. "At one point, we were working on 50 different things, which used to drive the others crazy – but it made me really happy. Depending on how I felt when I walked in one morning, I had 50 different things to choose from, and it's brilliant! ... Totally swimming at the tide, you don't know what's going to happen."

For Radiohead, revisiting the past would clearly not benefit the future, and their decision to split the album in two was seemingly the most artistically responsible approach. Most of the songs left off Kid A appeared on their next album, 2001's Amnesiac.

"They are separate because they cannot run in a straight line with each other, they cancel each other out as overall finished things," Yorke told the Chicago Tribune in 2001. "In some weird way I think Amnesiac gives another take on Kid A, a form of explanation."

Grunge Pre-Nirvana: 20 Things That Set the Stage For ‘Nevermind’

More From 101.9 KING-FM